Small Spruce on Black Pond (Olympus E 510, Zuiko 11-22mm f2.8)

Cross Country Skiing???…that’s too much work.

I am fortunate to reside in a portion of the eastern Pennsylvania Mountains (hills, really) where snow is fairly reliable from January through March. I also have a residence in the High Peaks region of the Adirondack Park in northern New York, where one can generally add a month on each end of the Pennsylvania snow season.

Since childhood, I have enjoyed snow sports of all kinds, but for the last thirty years, skiing, has been a dominant winter activity. It’s pleasant, that in both of the locales where I reside, that most of, my friends are also skiers.

I have been an avid downhill and Telemark skier in the past, but a bum left knee has left me somewhat hobbled in this regard. While allowing a few years to pass prior to undergoing knee replacement, I continue to at least be able to cross-country ski, which in some ways I enjoy more than its more glamorous sister sports.

Snow Squall near Rocky Falls (Olympus E 20)

Cross Country Skiing has several advantages. First, it’s cheap, both in terms of equipment and venue costs. To get fully outfitted for downhill skiing (skis, boots, bindings, and poles) could cost US$600-1000. I can find a nice touring cross-country set up ( the kind of skis you’d use on your local golf course or hiking trail) for between US $250-350.

Then there’s the clothing. Alpine skiers tend to use different clothing (warmer, less emphasis on breathability, more emphasis on style) whereas, if you’re already hiking in all seasons, cross-country garb tends to be an extension of your typical outdoor layering clothing strategy.

Some of my crusty old friends still insist on skiing in wool sweaters, and knickers with knee socks like we used to do thirty years ago. Oddly enough, wool works pretty well, except that everything tends to stick to it. You look like a snowman if you fall.

Then there is the venue. In the Adirondacks, a day of skiing at two Olympic skiing sites varies rather widely. At the time this was written (2011) a downhill ski lift pass at Whiteface Mountain is around US $80. By comparison, to ski at the Van Hoevenburg, Cross Country Ski Center (as well-groomed and full featured as anywhere in the country), costs a relatively modest US$20. Its trail system connects to the equally lovely Cascade Ski Center where a ticket is an even more reasonable US$12. In truth, resorts such as these are a luxury. Most of the time, I end up “backcountry” skiing on public land where typically there is no fee.

Chimney at John Brooks Lodge (Fuji S3, Nikkor 18-35mm f 3-5)

When I bring up the topic of cross-country skiing to someone who has never tried it, the invariable comment is something like: “that’s a lot of work”. Actually once you learn the technique, moving at a brisk pace over level or even rolling ground is fairly easy. Like all forms of athletic activity though, if pursued with vigor, it’s a formidable workout.

Photography from skis can be very fruitful. Whether on alpine gear at a downhill resort, or on a tour on Nordic skis, the surrounding scenery tends to be rather striking.

Behind Pitchoff, on the Jackrabbit Trail (Panasonic GH1, Lumix 14-45 f3.5)

Doing photography however, while pursuing any athletic activity has its problems. Active muscle tone and a bounding heartbeat can make obtaining sharp images a challenge. Camera stabilization is very important. Something as simple pausing for five minutes after exertion to allow your heart rate and “contractility” to subside a bit can help to avoid camera shake. Ski poles, tripods and, in fact any fixed object you encounter can be helpful.

It can be intimidating to carry hundreds, if not thousands of dollars worth of camera gear in a pack if you are not a confident skier. Hone your ski skills before packing up your most valuable gear before a challenging run. Until your pretty sure you’re not going to fall onto and crush your brand new point and shoot ( or fall on your D3 , and injure yourself), pack along more expendable equipment. If you’re not yet ready to ski with your camera equipment, snowshoes can be another, somewhat easier way to venture into the winter wilds.

Old Guy on Snowshoes

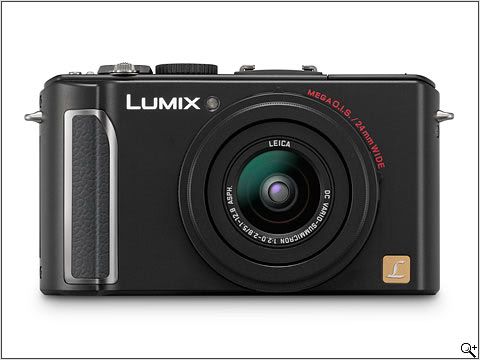

I really like the Panasonic G-series cameras for skiing because they are light, moderately priced but can still capture high quality images. They are also fairly sturdy, but I still think that they would deform in an accident, sparing my spleen.

I tend to carry camera gear in a large “fanny pack” with a shoulder strap over my left shoulder, and the hip belt tight enough to inhibit bag migration. When I want to shoot, I loosen the belt, and swing the band over my right hip, towards the front, where all of the contents are convenient to access. The Mountainsmith pack that I use fits a G series camera with several lenses, extra batteries and memory, a water bottle, plus room to carry a shed layer, all without disturbing my sense of balance.

Ice Fog, Arbutus Peak (Nikon Coolpix 4300)

Longer, more ambitious winter trips require gear that will only fit in a larger backpack. In this case, a smaller fanny pack can be carried up front, for quick access to your camera gear.

Skiing into remote areas allows one to observe and photograph even familiar territory in a whole new light, and get some wonderful winter exercise.

And it’s really not that much work.