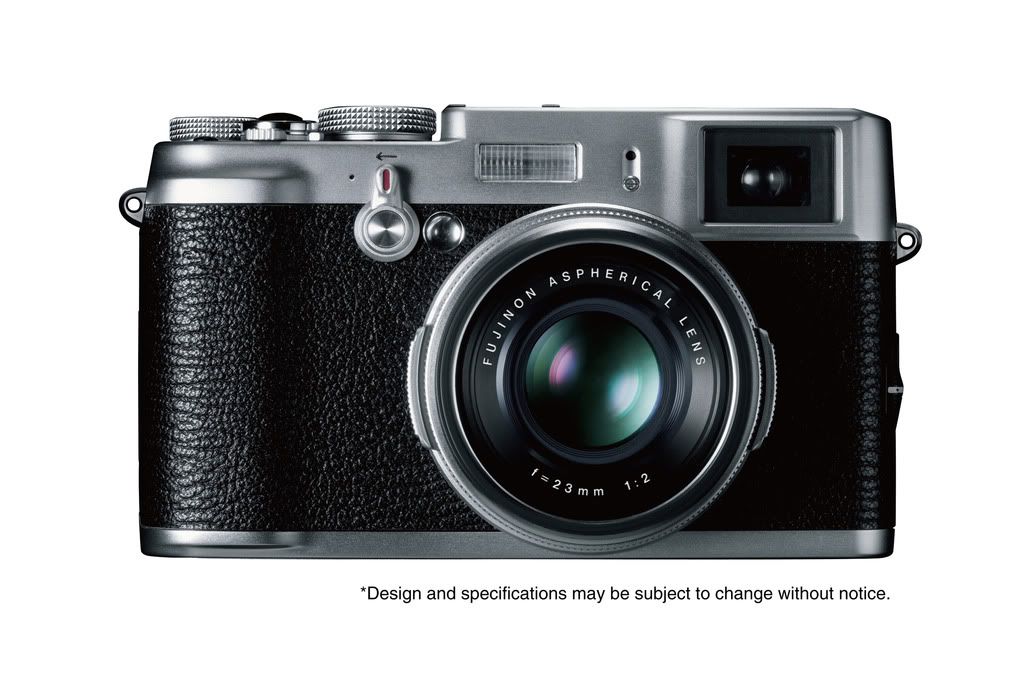

Front Street Summer Morning ( Fujifilm X100)

In the 1970s, a man by the name of Carroll Shelby went on sabbatical from his normal job, which involved promoting specially built high performance sports and racing cars, and developed a second passion into a nationwide following that persists to this day.

His passion was for the cooking of “Texas chili”, his enthusiasm led to scores of people discovering this passion within them,

Mr. Shelby has passed, but his legacy lives on, not only in the thousands of sporty cars that bear his name. It lives on, somewhat more obscurely, in an almost weekly ritual shared by of large groups of Americans, who packed their car with cooking utensils, and gather in cities and towns throughout the country, to cook chili, swap stories, drink beer, and, oh yes, to compete for the title of best chili. I was recently invited to attend such a gathering with award-winning chili cook.

Now I have always liked chili, and even fancy myself capable of producing a reasonable pot now and then. Then one day my friend Rich, or “Brooklyn” as he is known by his Pennsylvania friends(but probably not by his Brooklyn friends) explained to me, the art of competitive chili cooking. I realized pretty quickly, my own skills in that regard were at best, crude and unrefined. A couple of weeks ago he invited me to attend within a chili cook off in Harrisburg Pennsylvania, roughly 2 hours from my home. He actually suggested that I should cook of batch of chili on my own. I decided it might be better to watch one time and also to photograph the event.

I think I was right.

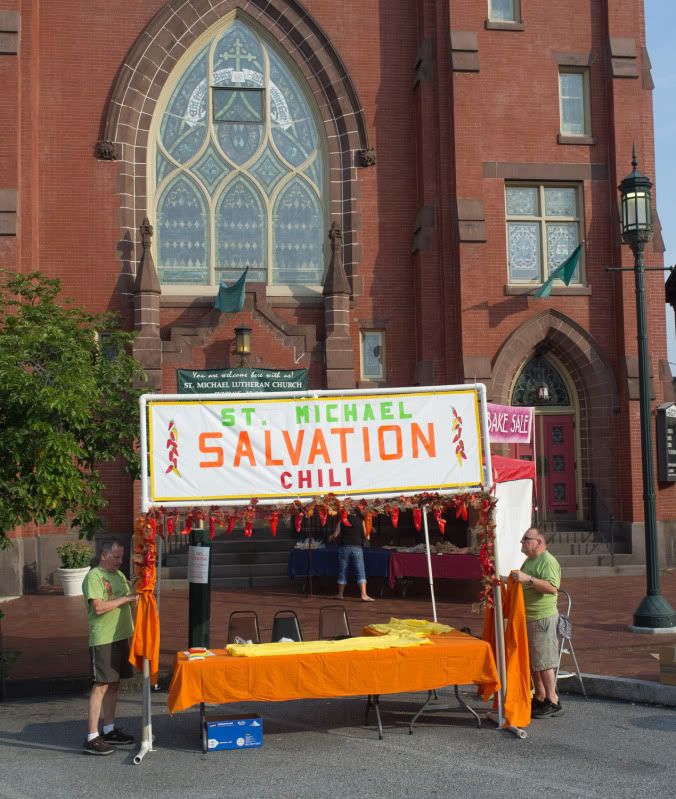

Salvation Chili (Fujifilm X 100)

This event was sponsored by the International Chili Society, a group founded by Shelby and his friends in Terlingua, Texas, in the mid 1960s. Their website is interesting reading, particularly the history of the society, which appears to have had a rather raucous founding in 1965.

It turns out, that the foodstuff that most people think of as chili, that concoction of ground beef, beans, chili powder and tomatoes is not thought of as authentic. The ground beef chili we know is referred to as “home-style”, and only recently has the ICS added a category for it in their judging. The traditional categories include “Texas Red” Chili Verde (green chili) and salsa.

The Teams Assemble (Fujifilm X100)

We arrived in Harrisburg around 8:30 AM. We were actually among the last to arrive slipping into the site next to Rich’s friend “Mad Mike”. Rich’s organization was impressive; we went from bare pavement to a functioning portable kitchen in about 15 minutes. The contestants sites varied in complexity from our rather unadorned workspace, to elaborately themed affairs designed to compete for the events “peoples choice” award.

We went to the organizers tent to register, received our sample cups, and various other premiums and souvenirs from the sponsors. Happily one of the sponsors was Miller beer who provided us each with a case of cold Miller light, that I noticed no one seemed to turn down.

Free T-Shirt (Fujifilm X 100)

I knew this was a good idea.

The rules of the ICS specify that all entries are produced on site in the time allotted (generally between three and four hours). Rich planned to enter a salsa, and a green and red chili and I watched with interest how he might accomplish this. He quickly cubed the beef and browned it, then chopped the peppers, tomatoes and onion for the salsa. Meat was then drained and dumped into the pots along with broth and pre-measured spices. Conspicuously absent from the pots were any form of beans, which are verboten in traditional chili entries. Even with no help from me (I did offer), Rich had the salsa done, and the pots simmering, in a surprisingly short period of time.

The “Set Up” (Fujifilm X100)

Though this was a competition, I was struck by the collegial atmosphere. People taste each others entries as they cook, loan each other supplies and spices, drink each others beer, and generally seem not overly concerned with the final results. From time to time one of the other contestants would gift us with novel snack food, generally involving things like peppers, bacon and cheese hot off their Weber grill. Two booths down was Trailer Trash Chili, a fellow entrant who fielded a veritable army of attractive young women in off-the-shoulder tee shirts and shorts to hand out home-style chili (and undoubtedly win votes for that “people’s choice” award).

Workin” the Crowd (Fujifilm X 100)

With all of this happening, I reached deep into the cooler for a cold beer and quickly decided that this was a truly pleasant afternoon.

Just a “Dash” More (Panasonic Lumix GH1, Lumix 14-45 f3.5)

By Mid afternoon, all of our entries were in the judges hands. It was now time to visit the booths, and sample the various competitors’ efforts. Both the “reds” and the “greens” that I sampled had a definite commonality, but all were subtly different booth to booth. All had some “bite”, but none were particularly “hot” for fear of obscuring the flavors that they worked hard to develop. The best, particularly Rich’s and Mad Mike’s creations, had a robust texture, and offered a complex chili taste with just enough “kick” to induce a modest forehead sweat, after several spoonfuls.

Another Booth ( Fujifilm X100)

Our team fared a disappointing third for Texas Red, but Mike one first for his “Green” entry which, given the tasting I did, was an award well deserved.

My buddy Brooklyn wants me to enter at least one category on my next trip with him, perhaps next season. I think I just might. I’m less intimidated now that I have seen it done. Who knows, I might get lucky.

Mr. Lucky (Fujifilm X100)

Win or lose, I will be only too happy to participate in the festival of good fellowship, great food, good-looking women, and free beer that marks an ICS Chili event.